“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” George Santayana

“But there are no bacteria in Mars, and directly these invaders arrived, directly they drank and fed, our microscopic allies began to work their overthrow. Already when I watched them they were irrevocably doomed, dying and rotting even as they went to and fro. It was inevitable.” H.G. Wells – The War of The Worlds.

Introduction

I started writing this about four or five years ago and, like so many essays that I’ve begun and saved in my drafts bit, it was just festering. I’ve not published anything on here for getting on for a year, but that doesn’t mean I’ve not been writing anything. I’ve got a couple of Vietnam movie essays half done, one about cricket, another one about Baroque ‘n’ Roll, and all manner of things in-between . However, mainly what I’ve been doing is writing and recording songs, which is going pretty well so far. I like doing different things, and I get into these different things to a great extent, and then I get into something else. I wear myself out a bit. Currently, I’ve got about fifteen songs written, eleven of them recorded – mainly – and I’m faffing with lyrics currently. With these essays, I don’t really edit at all. I don’t even read them most of the time. They’re 99.9% first draft. The notable exception being the Billy Liar one, on account of I belatedly realised that I was full of shit on that one, and I wanted to put it right. The rest of them are either true accounts, or just flannel about pop music, mainly. Lyrics though? I’ve written a lot of songs over the years, and some of them I’ve been quite pleased with – musically and lyrically. However, the lyrics I end up with are always about the third or fourth draft because, I suppose, you just come up with any old crap when you’re coming up with the melody. While some of the original words inevitably remain – because they work best with the melody – I end up changing the majority of them at least twice. Anyway, this hasn’t been edited or checked for anything, like almost everything else on here.

Hippy Boy!

It started being about Hippies and what that meant to me, and then it moved into being about Crosby, Stills & Nash’s first album that I changed my mind about at least twice, and then being about the parallels between the first and second summers of love, and then about War of The Worlds.

In short(!) the usual meandering crap that I have to empty out of my continually rabbiting brain in order to get other things done. Like writing and recording songs. Like this blog thing, I don’t do it for any reason other than I like doing certain things, and if I don’t, I go a bit mad. Ah well, could be worse, eh?

When I was seven or eight my mother bought me a pencil case for school. More a bag, really. A white vinyl bag that had blue paisley psychedelic flowers on it. I hated it. The reason I hated it was because, like most seven or eight year old boys, I didn’t have the confidence to pull off anything remotely approaching sensitivity in terms of my exchanges with my friends. The closest any of us got to brotherly love was verbal and physical abuse. Anyway, she made me take it to school and I was ribbed mercilessly for it.

Another thing she got me and forced me to display in public – at a similar time – was what she described as a flower power tie. I can’t remember any specific occasions on which I wore it, but all of them would have been under sufferance.

The thing was that at that age, the year would have been either 1978 or 1979, flower power being but a distant memory for most people and not any sort of memory at all for me, having been born three or four years after such a thing had been accepted and shortly thereafter rejected by the mainstream.

I’ve previously alluded to the reality that, as the person who bought my clothes for me, my mother also picked out decidedly unfashionable trousers for me, both for school and for larking about in. When I say ‘unfashionable trousers’, what I mean is that they were, if not flared, then unacceptably voluminous.

With hindsight, my mother’s reference point for tight trousers would have been those worn by the spivvy rockers of her late youth which, in her mind, were inextricably linked with bike chains as weapons, motorbikes and greasy duck’s arse quiffs.

Evidently, my mother had been quite taken by the hippy ideals of the mid to late sixties, when she’d have been in her mid twenties and, like many of us, what had resonated with her had been the love and peace schtick, but probably not the drug element so much.

I’ve also written about the concept that the beautiful people’s scene probably didn’t have that much effect (beyond the width of trouser cuffs) outside of that London. Or LA, or San Francisco or most places that weren’t fishing ports on the East coast of England. Having said that, there are photographs of my mother in 1966 – when she and my dad married – in which she would have given Joni Mitchell a run for her money, at least in terms of the shy faced, sylphlike, long, poker straight hair down her back vision of beatnik beauty of the mid sixties, so maybe she bucked the Hull trend of beehives and headscarves that were more or less ubiquitous even into my time at school. She certainly looked like she’d bought into the hippy look, even if it was only the look and not quite so much the retiring, easy going spirit of Woodstock, because she had absolutely no truck with any of that.

Me? If I had no truck with the spirit and ideals of peace, love and hippiedom, I had even less with the accoutrements that went with it – at least as far as the image I wanted to project onto the world at large went.

Early experiences affect your later viewpoints, inevitably. And perhaps that explains my outright later hostility to Crosby, Stills, Nash (and Young).

Again, there’s not much sense in that viewpoint beyond an early aversion to flower power in terms of at least pencil cases and ties because, once I started getting into music, I gravitated swiftly towards the bands from which CSN(&Y) emanated.

I came to those bands in the order of their later supergroup’s initials. David Crosby had been booted out of The Byrds and I was (and remain, much to the chagrin of everybody I’ve ever played in a band with) very much into The Byrds.

My route into them was via The Smiths. Johnny Marr was, and still is, thought of primarily – and unfairly – as a predominantly jingly jangly guitar player despite plenty of evidence that points towards his playing incorporating – at least – rockabilly, funk and folk. Anyway, he was always being described as sounding Byrdsy, which meant Roger McGuinn, which meant heavily compressed Rickenbacker 12 string guitars chiming away.

I got myself a compilation called The History Of The Byrds which, with hindsight, isn’t the best introduction to them because far too much of it focuses on their later – really shit – descent into really bad country and western stylings. I don’t mean Sweetheart Of The Rodeo or Untitled, because they’re great. Well, I think they’re great now, I didn’t then. It’s a double album, The History Of The Byrds and the first record’s great. Well, it’s pretty good even if it doesn’t include Feel A Whole Lot Better, which all Byrds’ Greatest Hits ought. Naturally, it’s got Mr Tambourine Man on it and enough of the jingly jangly early years’ material on it, so I was into it. It also has Lady Friend on it, which is a Crosby song and I liked that a lot.

There are a lot of Byrds albums and, from what I could gather, there was a lot of crud on most of them, so I just stuck with that one and asked John at Golden Oldies who else I might like, bearing in mind I’d enjoyed The Byrds. He recommended Buffalo Springfield and sold me a greatest hits by them – another double album. Stephen Stills (and Neil Young) were in Buffalo Springfield.

When I’d told John I was into the Byrds, I had specified that I liked their jingly jangly, earlier stuff and not the country and western crud that clogged up about 80% of the second half of History Of The Byrds, so I was expecting more jingle jangle.

If you’ve listened to much Buffalo Springfield, you’ll be aware that they’re not remotely jingly jangly. Not like The Byrds at all really. Harmonies, yeah. Chiming, jubilant 12 string introductions, not so much. I liked a couple of songs on it – For What It’s Worth and Expecting To Fly but, mainly, I didn’t really like it.

Back at Golden Oldies a couple of months later, I was after a Hollies greatest hits record because I had a bit of cash and Paul Taylor’s mam had played me their 1970s version at her house and I’d taped it and not paid much attention to it after being initially quite impressed. There was a definite golden period for The Hollies that was bookended in the early days by Merseybeat by numbers, afterwards by cabaret, MOR 1970s schlock. Anyway, John remembered I’d enjoyed The Byrds 12 string jangle and pointed out as I handed over the sleeve of Greatest Hits (And More) that Tony Hicks played a 12 string on quite a few of their big sixties hits.

I enjoyed The Hollies’ greatest hits a lot more than I had the Buffalo Springfield’s, even if some of the early and late stuff was unacceptably trite to my delicate lugholes.

And yet, as the years went by and as I dug deeper and deeper into the world of the psychedelic sixties, I studiously avoided Crosby, Stills, Nash (and Young). Because they were fucking hippies, man. Even though I was even more into The Byrds – I’d got hold of most of their albums and really liked a lot of it – I’d not bothered with Buffalo Springfield’s or The Hollies’ albums.

I read a book about The Byrds and Crosby got slagged off quite a lot by Roger McGuinn – and the everybody else who’d been in The Byrds over the years – so maybe that was it. I might have felt a bit of loyalty towards The Byrds and, like a spurned lover, was determined to not pay any attention at all to someone whom they’d kicked out because he was a twat.

One night before going to Spiders I was at Dave‘s house, sitting with his mam and dad in the living room because Woodstock was on telly. I’d not seen it before and absolutely nothing I witnessed that night persuaded me that I’d been missing out on anything worth listening to. Not that I saw all of it, but the bits I did see made me think that, if anything, I’d been much too lenient in my already damning opinion of it, despite not having seen any of it prior to that. By that point, I wasn’t against the idea of it – peace and love, maaaan – but I found the reality pretty off-putting.

Then a couple of years later, when I was going out with Poor Sharon, she sent me a compilation tape she’d done for me. It was a sweet idea. She’d taped songs that made her think of me, such as The Kinks’ Plastic Man, which we’d spontaneously harmonised on behind the hot dog counter at The Odeon, The Pretenders’ Back On The Chain Gang, because we’d bonded over a shared enjoyment of that sort of grunting on records, and a couple of others that made her think of me. Most irritatingly was You Are So Beautiful To Me by Joe Cocker because of its strongly implied message that nobody else thinks you’re beautiful due to the superfluous ‘to me‘ at the end of the chorus. I thought it was a bit of a cheek, and I can’t stand Joe Cocker, but them’s the breaks, eh?

As we’d not been going out long, she was going to struggle to fill a C90 with records that had some sort of meaning between the pair of us so she also taped me some stuff that she’d enjoyed from being a little kid. Stuff her parents had played, I suppose.

Most of them were very bad indeed – John Denver, MOR 1970s Fleetwood Mac and the like. But among them was Marrakesh Express, which stood out because, I suppose, I really enjoy a gurgling Hammond organ. The guitar playing was pretty unusual too and, as it was going through a Leslie speaker (which I’ve always been partial to), that tickled my fancy too. Being loved up, as I was, did no harm either in terms of the overall ebullience of the record. It turned out to be a single from the first Crosby, Stills, Nash album. Ah.

Back to Golden Oldies, John sold me a second hand copy of it and, squinting in the glorious sunshine that was struggling to pierce the grime through my bedroom window at Desmond Avenue, obligatory cup of tea in hand, I shook my head in wonder. How could I have been so stupid? Why had I decided that listening to anything that David Crosby had anything to do with would have been in some way disloyal to The Byrds? In the 1990s, long after they’d split up? Beats me, but that’s what I’d been doing and now, tea cooling but not passing before my now slackened jaw, I marvelled at it. This was everything I liked about music: Leslie treated guitars, beautiful harmonies over optimistic, happy songs with unconventional structures.

I liked, even more astonishingly, almost all of it on the first play. Turning it back to the first side, I played it again to see if I’d just become (more) confused (than usual). Apparently not. Well, bugger me.

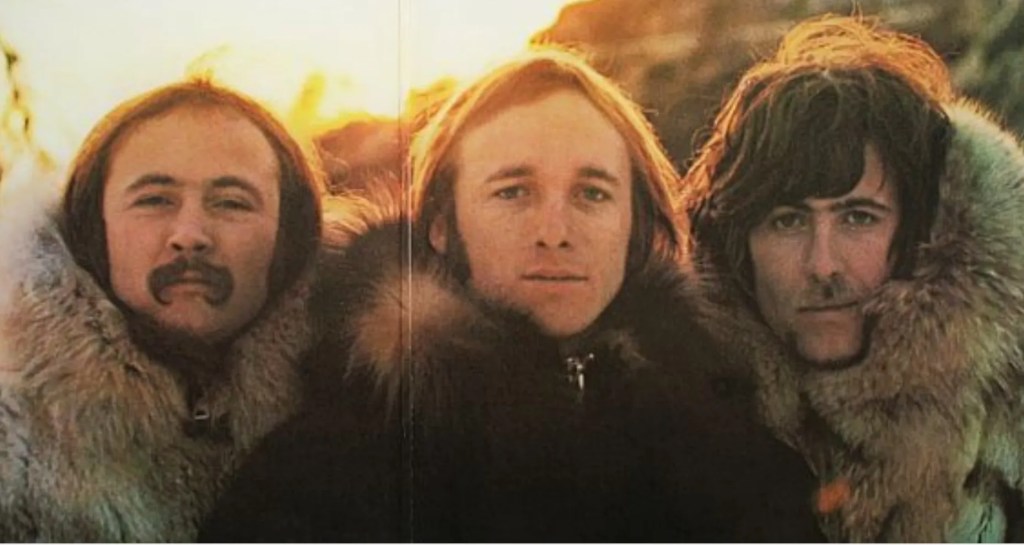

Having spent so long studiously avoiding it – which hadn’t been very difficult, presumably it was so much of its time that it dated very quickly and consequently didn’t get played much anymore, at least nowhere I was aware of – I wondered if I’d just gotten confused and played it to Ploggy when he came home. He said it was shit. Hippy shit. I could half dig that. Hippy, it most certainly was. If anything, it’s the ultimate hippy album. Shit though? I had my doubts. Slick? Definitely. This wasn’t some tossed together strummed acoustic guitar scrubbing and chanting about Aquarius or patchouli oil hippiesploitation thing, this was polished. This was crafted, no, exquisitely crafted. Thinking that put me off it a little bit, but I remained convinced. This was hot shit, whatever Ploggy said. Mind you, at that point in time, Ploggy had been trying to convince me that the Thurman album (remember them? No, of course you don’t. Who does?) was the real deal. It wasn’t.

My best mate Dave was living in Gloucestershire with Gill by that point and he had better taste than Ploggy but when he came up to visit and I played it to him, he said it was nunty. And shit. I was much more interested in Dave’s opinion and not just because he didn’t give a shit about fucking Thurman either. I could see where he was coming from with his nunty verdict but, apparently, I didn’t care. Apparently nunty was now alright by me. I expressed mild concern about myself. In private. But I didn’t chuck it out. Of course I didn’t chuck it out: I never chucked anything out. Not records anyway.

Suite: Judy Blue Eyes, the opening song on it became my favourite. A conglomeration of bits and pieces that Stephen Stills bunged together in tribute to Judy Collins, who was a popular folky artist of the time and a few years older than he was. All three of CSN were in relationships – or had just begun them – at the time they wrote and recorded the songs on it and, in a way, that’s one of the nice things about the record. The early days of a relationship – one of the joys of being alive, I suppose, and this album sounds like that feels.

Well, most of it does. A lot of it does. Suite: Judy Blue Eyes does; Marrakesh Express doesn’t particularly but as it’s about the excitement of discovering a different culture, it sort of does too; Guinevere does, even though it’s about three different women, but that’s The Croz, as some people liked to call Crosby, for you; You Don’t Have To Cry does; Pre-Road Downs* sort of does; Wooden Ships sort of does too, even though it’s about a post-nuclear attack in which all the beautiful people sail off on their expensive boats and form some sort of aquatic Woodstock while all the fucking boatless plebs disintegrate on land – which could be some kind of metaphor for the bubble you find yourself in, in the early days of romantic relationships; Lady Of The Island is, to be fair, so nunty, I can’t even bring myself to contemplate whether it’s about burgeoning relationships or not; Helplessly Hoping does; Long Time Gone and 49 Bye Byes don’t really. But most of the album has a seam running through it that’s redolent of blissful young love. If not specifically that, it’s about being excited about new things. The possibilities that come with youth and fresh beginnings. Bearing in mind how all three of them had recently left bands, been kicked out of bands or had their band implode on them, perhaps that’s not too surprising. On the other hand, of course, depending on your attitude, you could see the end of one thing as being something to worry about, but Crosby, Stills and Nash evidently didn’t. Not at that point in time, at least.

And it is about that, but it’s also not. It’s also about fear – which I admit I have a tendency to suggest that pretty much everything is about. It’s all very well, The Croz getting uppity about getting kicked out of The Byrds when he was writing the best songs out of any of them – as far as he was concerned, at least – but, as human beings, to preserve our fragile egos, we often tend to stick our chins and chests out after we’ve been rejected and tell everyone that we’re not even bothered and – actually – whoever kicked us out was doing us a big favour because we deserve better than them.

*I’ve been thinking about writing a post about ill advised rocking out records (edit – I’ve done a load of those prior to sticking this out there), of which Pre-Road Downs is a prime contender. Graham Nash isn’t a great songwriter, even if he thinks he is, but he’s a lot better at writing soppy, slowish, pop songs than he is at writing anything remotely rowdy. It must be obvious by now that I’m pretty far from some sort of gurning rock beast by now but I’m Lemmy compared to Graham Nash. There’s something I find simultaneously cringeworthy and appealing about gentle people who decide that they’re going to start grinding and gurning away onstage. Something that I feel fairly ambivalent if I’m being completely honest. I don’t like it when it happens but, on the other hand, I can’t take my eyes off it either. And there is something about the incongruity of – especially – men with high pitched, clear voices – who try their hand at rawk. Man. Colin Blunstone out of The Zombies is another one who ought to get a refund on any leather jackets he’s wasted his money on. Have I ever had a leather jacket? No. Why? Because I, too, am much too fey for all that.

Well, you could say that. I have said that, even though I don’t really believe it anymore. Not about my being fey though, nothing much changed there. If anything, I’m even worse now than I was then.

What I believe now is that what I thought about it before I’d heard it was probably more realistic. Which is to say that hippy, as an ideal, is a load of shit. And I don’t just mean when your mum makes you take a hippy pencil case to school in 1979 or wear a flower power tie when you have to look smart outside school. If only. If only…

The nastiest angle I have on things like the first Crosby, Stills, Nash album is that it’s not about peace and love and flowers at all because it’s really about me, me, me. It’s a capitalistic statement of intent. It expressed a desire to grasp things for yourself, while justifying that all those other people are just breadheads (maaaaan) and that CSN might have wanted the same sort of things as your typical businessman in his suit, actually, they were better than him because they were artists. Man.

That could be seen as unnecessarily cruel but the reality is that when the three of them jokingly talked about calling themselves The Frozen Noses, what they were talking about was how they were all coked up constantly. Cocaine being the most me, me, me drug on the planet doesn’t really make me think that some sort of Hippy Concept Of The Future would be such a groovy place to be, on land or at sea.

And that’s part of the issue that I have with the hippies: it’s ostensibly all about coming together and sharing and free love and all that but I can’t help but think of it as being a bit like a Conservative Party election manifesto. It might sound reasonable on the surface but when you think about what the reality of these ideals would consist of, it doesn’t really sound too appealing. At least not to me. You know, sharing sounds great – and it should be – but some people’s idea of sharing consists of the idea that you can share your stuff with me and I’ll keep my stuff to myself. Coming together – not in a rude sense – sounds nice, but Woodstock looked fucking awful. Half a million people without a single toilet between them. I don’t mind a crowd, but I quite like a bit of peace and quiet too and I don’t know how much of that was on offer at Woodstock. I share my house with two people and a cat and, frankly, the only time there’s anything remotely approaching peace and quiet is when it’s just me and the cat. Presumably it’s pretty quiet when everybody except the cat’s out too, but he’s too quiet to tell me about that. It might even be too quiet when it’s just the cat because he always seems pleased to see me when I come home. And free love? Pfff. I think we all know what that meant and it doesn’t sound too appealing to me.

If I’m going to be a little bit more vapid about it, I suppose that Hippy music was really about something a lot more simplistic than any of the things I’ve written about so far – sunshine.

The hippy music of 1967 gets lumped together under the banner of “The (first) Summer Of Love” and I don’t think that’s an accident. Let’s have a look at the big, popular, classic hits of The Summer Of Love shall we?

Scott McKenzie – San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)

The Mamas & The Papas – California Dreaming/12:30 Young Girls Are Coming (To The Canyon)

The Beach Boys – Good Vibrations

The 5th Dimension – Aquarius (Let The Sunshine In)

Traffic – Paper Sun

Petula Clark – Don’t Sleep In The Subway

These are all songs about sunshine and summer and how great it is to sit in the park with your groovy friends, checking out groovy chicks in their groovy threads because everybody looks better in summer. Or you’re more pleasantly disposed towards them or something.

And, to me, that’s what hippy music tends to be all about – sun worship and beautiful people. And I can dig that because it’s great when it’s sunny. As I type now, the sun’s out and I like that a lot better than when it’s not. Even though I’ve got the curtains drawn because I’m half watching cricket on the telly.

The summer sun means optimism, doesn’t it? A sunny day is a day that’s pregnant with possibility – you can go places, you can do things and wherever you go and whatever you do, it’ll probably be alright – at least – because at least it’s not raining. I like the idea of being optimistic, even if I’m a bit scared of it too – and slightly battered by what time does to the (once) optimistic. I’m not complaining, but I am a bit more wary now than I used to be.

It’s no coincidence that if Hippy has a home, it’s on the west coast of America. Even though Woodstock was near New York on the east coast. Actually, there’s no ‘even though’ about it – Woodstock was blighted by mud and rain which wouldn’t have happened on the west coast. There were numerous west coast festivals of hippiedom, especially in San Francisco, and you don’t hear about the rain and the misery of those, do you? Apart from The Rolling Stones at Altamont, but that didn’t happen until December 1969 anyway and The Rolling Stones’ brief (and under-rated) hippy phase was something they were already pretending hadn’t actually happened at that point. Crosby Stills Nash and Young played at Altamont too, although you wouldn’t know that from watching the film of the concert tour (Gimme Shelter – highly recommended) because they’re not in it at all. And, whenever anyone talks about Altamont now – and when they talked about it closer to the time, too – nobody suggests that it all went to shit because it was cold, do they?

Up to this point, then, I’ve suggested that the Hippy ideal had a public image that it liked to present to the world in general that, basically, was all about sunshine, peace, love, flowers, and caring, sharing, beautiful people and that there was also an underlying feeling that went with it, and that feeling wasn’t a very nice one, consisting of selfishness, greed, and feelings of superiority and entitlement.

I started this post mentioning how the hippy era was long gone by the time I had any idea at all about what was going on in terms of culture, and it had. However, fashions cycle around and around and, inevitably, there were always elements of hippiedom that, inevitably, would return, and they did.

Diversion – Mods -> Hippies -> Baggy -> Britpop Fashion.

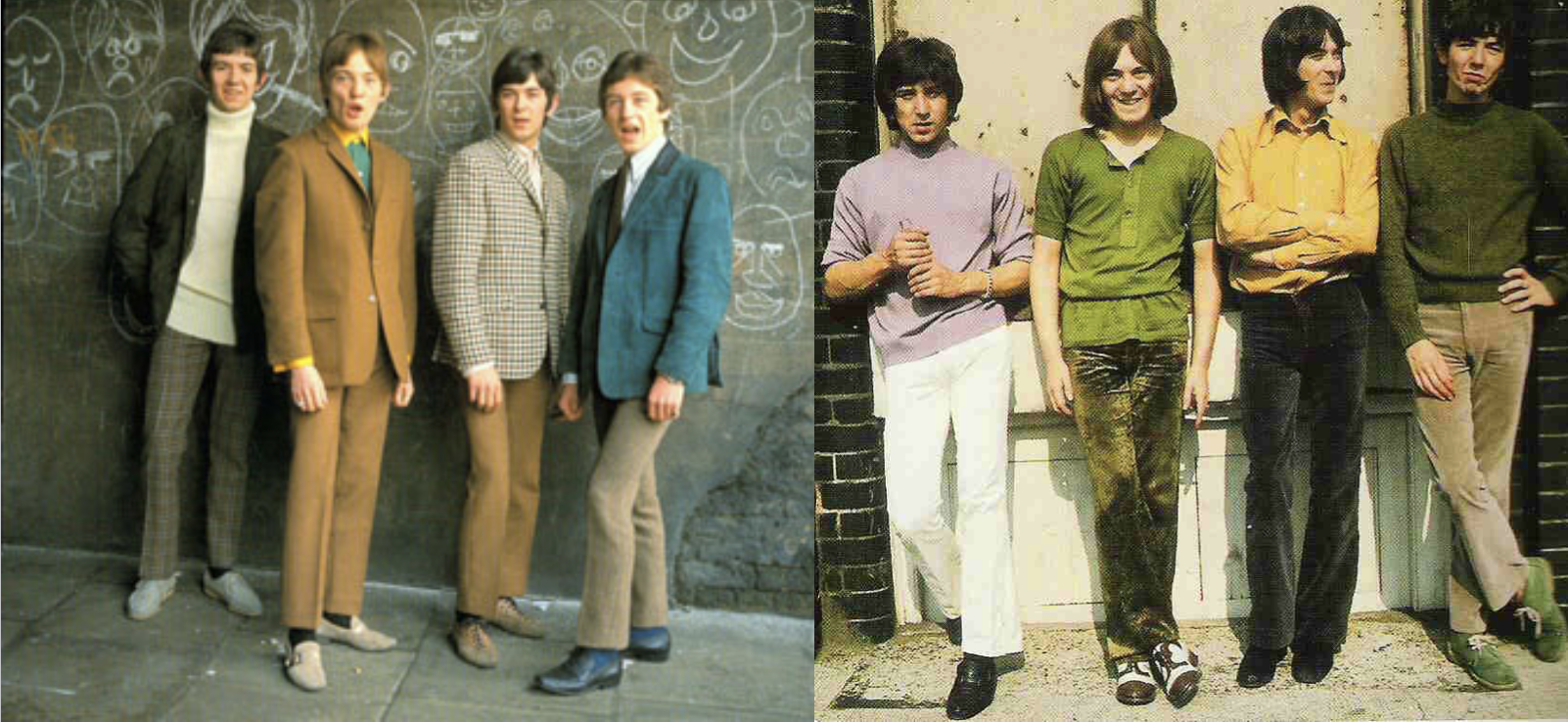

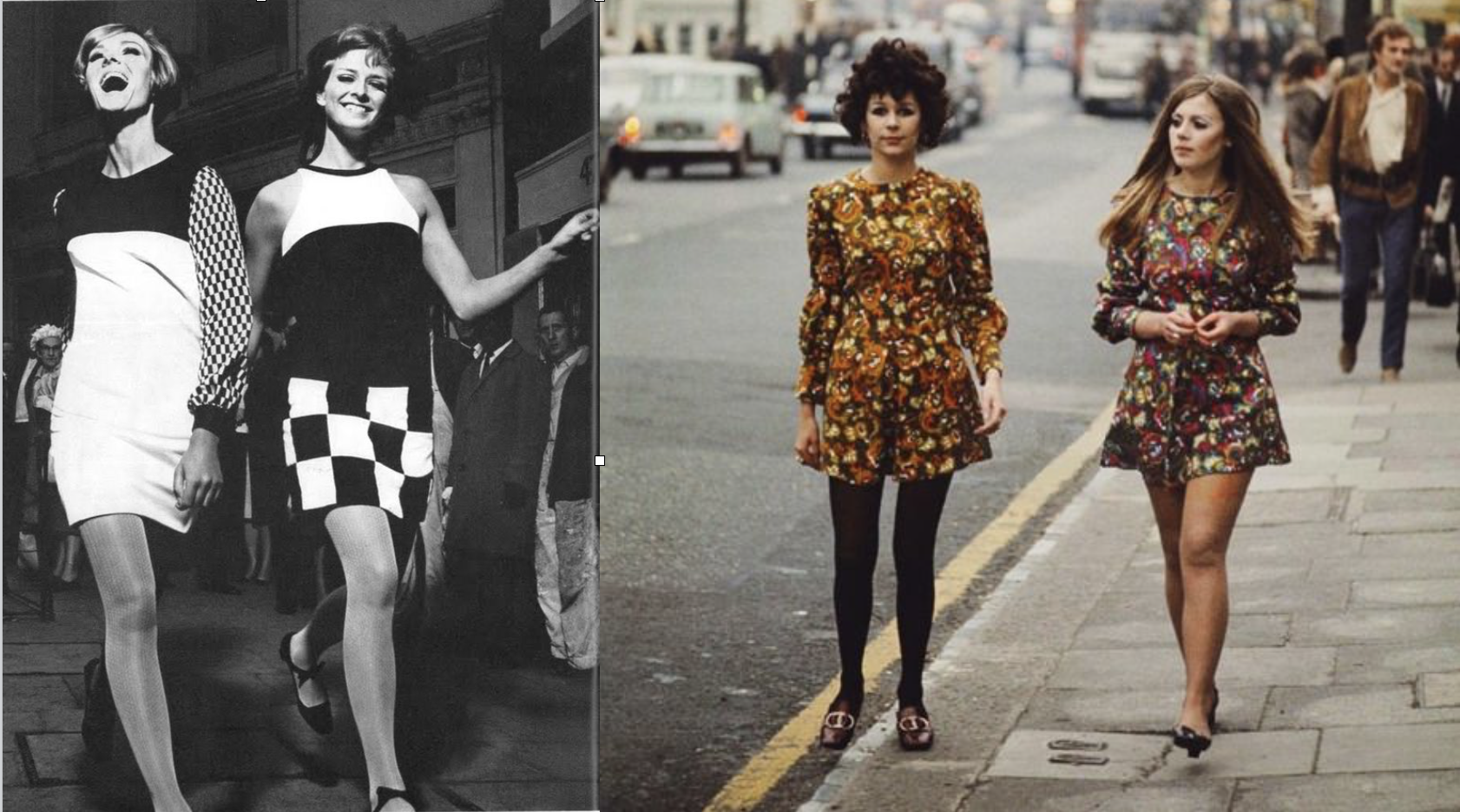

The ultimate symbol of the hippy was, as many ultimate symbols are, the trousers and the shoes. All fashions are reactions to what’s gone before and for hippies, they were reacting against, I suppose, modernism. The mods. And the rockers, too, I suppose, as both subcultures’ trousers were on the snug side, from top to bottom. Naturally, the tightness of both the mods’ and rockers’ trousers were a reaction against the – not exactly sexless, due to women not really wearing trousers at all, Katharine Hepburn not included – baggy pants of their parents’ generations. The equivalent girls’ fashions did permit trouser wearing, unlike their parents’ generation, and that was a reaction, but shorter skirts came with the mod fashions – Mary Quant and Twiggy and all that, it was a mod thing. Bell bottomed trousers were a reaction against the drainpipes of the earlier sixties – black and white sixties – but they couldn’t just wear their parents’ trousers again, could they? The point of their parents’ trousers was modesty – no chance of seeing bulges around the groin. The tightness remained from the waist to the knee, at which point, whoomph! Out they went. Tight and loose. Hippy girls could still wear short skirts if they felt like it, but they could also go for a much longer hemline. The point was the same as the trousers: it wasn’t so much about the length, it was about the width. Mod skirts were pretty tight, as well as short. Hippy skirts were looser altogether.

Patterns changed too. Whereas the mod ideal – for men and women – tended towards the conservative (clean living under difficult circumstances), with the closest thing to psychedelia was the introduction of Op-Art patterns, especially on dresses, most of it was either plain or houndstooth checks. If the Hippy era had a pattern, that pattern was paisley.

It’s a subtle difference, as well it might be – the mods were a far greater reaction against their parents’ clothes than the hippies’ clothes were against the mods. Who were the hippies? The hippies were what mods turned into, largely – as you can see from the evolution of the Small Faces’ clothes. The same thing went for The Beatles, who went from rocker to mod, to hippy clothes.

Though the early 1970s retained remnants of the hippy styles, right up to around 1976 and punk, you didn’t see much in the way of anything remotely hippified throughout the 1980s, until around 1989.

At that point, ecstasy was the drug du jour for the youth and the effect it had, on clothing fashions at the very least, was monumental. Hippy fashions, following years in the wilderness, were back. Sort of. Ecstasy wasn’t a hippy drug, but marijuana and LSD were. As I’ve mentioned, for the likes of Crosby, Stills and Nash, cocaine was another big drug – but it wasn’t for very many ordinary people. The mods’ drug of choice was speed, of course.

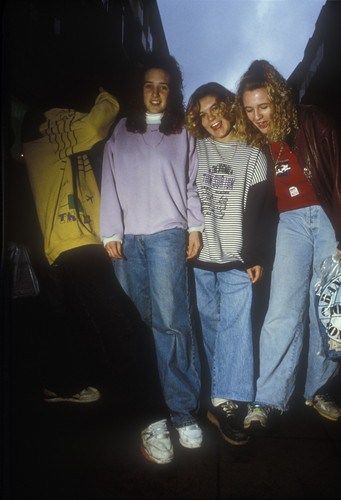

Oddly enough, the (in terms of fashions at least) fashions for girls followed a different pattern. In the first summer of love, loose fitting clothes were in. It was the same in 1989, except you didn’t really see many girls who were into the Manchester/Baggy subculture wearing dresses or skirts – at all.

Of course, it’s easy to suggest with hindsight that, in 1989, all of a sudden, everyone started wearing flares again, because the reality is that they didn’t. By any stretch of the imagination. Similarly, the photograph above implies that all girls stopped wearing dresses and skirts, when they didn’t. Obviously, some of them did, but plenty didn’t. In fact, the majority didn’t because the Madchester/Baggy thing was very much a subculture that didn’t really have a huge effect on the mainstream until around five years later, when Britpop fashions were sort of mod-casual, through a filter of the less outlandish baggy fashions that went a little bit far for some people. Flares were still okay, but they tended to be more similar to the hippy flares, inasmuch as they were tighter around the groin, down to the knee. Girls wore dresses again. Sex was back. And so was cocaine, but ecstasy was out, as was LSD.

In short, hippy rose from a wish to liberate themselves from too much uniformity and restriction, hence the clothes, the music, and the drugs – were all about expansion – wider trousers, floatier dresses, longer, less structured pop music and mind expanding pot and acid. Baggy was a return to all of those things, except it was all rather sexless, oddly enough. By the time Britpop happened, some of the liberating tendencies that Baggy had brought back were reigned in again – the groins of the trousers, the prevalence of LSD and marijuana. During Britpop, the longer excursions of the baggy bands: Fools’ Gold, The Stone Roses’ biggest hit single was nearly ten minutes long. Weekender by Flowered up was nearly thirteen minutes long, and they weren’t the only bands bringing back the extended jamming last seen played by men wearing flares and cheesecloth in the early 1970s.

Which is to say, despite the ubiquity of Baggy bands’ James Brown sampled beats and interview soundbites of “There’s always been a dance element to our music,” for some of these next generation hippies, Prog was where they were heading. Not in terms of changing time signatures or lyrics about goblins and wizards but, again, in terms of size. Wide trousers, long records.

End of Diversion

The hippies of the sixties, who I’m talking about mainly, they didn’t really do that. Okay, The Beatles had Hey Jude (7.11), The Stones had You Can’t Always Get What You Want (7.31), and The Who had Won’t Get Fooled Again (8.33), but these weren’t any of these bands’ summer of love hippy records, these were too late for that, really – late summer ’68, December ’69, and August ’71. Alright, the hippy thing hadn’t died out entirely, but it was a different sort of hippy thing by then, and anyway, they were all English bands.

CSN, despite Nash’s northern Englishness, were an American band really. Their debut album came out at the end of May ’69, which was a bit late for the summer of love, but right on time for self-absorbed cocaine driven chuntering, which is what is was.

Importantly, it still sounded like summer, even though the inside of the gatefold sleeve has them in winter coats, looking a bit cold.

By the time their first album came out, the summer of love had left us with flared trousers, long hair, and a vague sense that The Age of Aquarius wasn’t really going to happen in the way that The 5th Dimension had funkily suggested it would. Woodstock wasn’t quite the end of it, that accolade traditionally goes to The Rolling Stones at Altamont later that same year – 1969.

Diversion – Love Has Won

I’m a sucker for a cult documentary, and when I say “Cult Documentary”, I don’t mean a documentary that has cult appeal, like the Mondo films, or like Dig! about The Brian Jonestown Massacre and The Dandy Warhols, I mean documentaries about people who’ve been in cults.

I can’t imagine being in a cult, personally, but I’m interested in what sort of people would be. Love Has Won is about a group of modern day hippies whose leader, Amy Carlson – basically a party girl who couldn’t be arsed with the day to day grind of work and being a grown up (and fair dos, it’s pretty boring a lot of the time) because she wanted to get pissed, take drugs and have people run around after her. She and a bunch of her followers set up various communes where they got pissed and took drugs all day, in between selling a load of expensive hippy tat on the internet. Including colloidal silver, which ended up killing Amy Carlson.

So far, so typical, but what it showed in particular was how a lot of her acolytes were, basically, lost, gullible kids who had a nice idea, providing you’re a fucking moron with no critical skills.

Most of them. Not all. Almost straightaway there was a dude who didn’t really seem too taken in by all the hippy dippy horseshit, but who did seem quite interested in looking after the vast amounts of money her organisation was raking in.

A little while into it, someone else turned up, and he looked like that crocodile onto whose snout a chicken has just wandered. His eyes must’ve lit up when he came across that set of suckers. He, and I can’t be arsed to look his name up, was an opportunist who was quite happy to don the hippy uniform and say the right things, but basically, as with all cults, the majority of their members were just ripe for the picking. Rubes, schmucks, you dig? Suckers. You’d have to be, wouldn’t you? and there are a lot of people like that around.

End of Diversion

Which is a problem because if these people are ripe for the picking by cults, it’s inevitable that these cults are ripe for the picking by unscrupulous non cult members. Obviously Gimme Shelter – the film of The Rolling Stones’ ’69 tour that culminated in the bloodbath of Altamont. As their final show goes on, the looks of disbelief on the faces of the hippies in the crowd are, well, quite funny in a perverse sort of way. Meredith Hunter getting stabbed by Hell’s Angels wasn’t funny, but that Hell’s Angel who’s having a bad trip at the side of the stage and is freaking out as Jagger warily watches him – that’s funny. As is the dog that wanders across the stage mid song. But most of it’s a bunch of long haired, bespectacled students shaking their heads and asking Jagger “Why?” as he sings something violent.

It’s mean of me, I suppose, what with hippiedom being an adults’ version of childlike innocence and wonder to take the piss and enjoy it on that sort of level, but if hippiedom wasn’t so selfish and cynical at heart, maybe I wouldn’t enjoy it quite as much as I do.

I mean, I love an awful lot of records, films and books of that era – it’s my favourite in a lot of ways – but I don’t believe it. I was into Star Wars when I was a little kid, and I didn’t believe that was real either. It doesn’t affect my enjoyment of either thing, the lack of depth or reality to any of them.

People suggest that Hippy was never going to last, and I agree with them, but not necessarily for the same reasons that other commentators do. For me, Hippy is fundamentally about nice weather and flared trousers, and that’s about it. Maybe doobies. Probably doobies, in fact. In actual fact, Hippy is primarily about sitting in the park on a beautiful summer day in a brightly coloured t shirt, flared trousers, casual shoes, listening to music from 66-68 on someone’s ghetto blaster, smoking doobies with groovy chicks.

Which sounds pretty good to me. The problem with that little scenario is that, after not very long, a bunch of dickheads are going to turn up and spoil it because it’s easy to do that. which is exactly what happened to Hippiedom in general in the late sixties. The hippies can’t do anything about it because they’re all about non-violence and peace and love, maaaan. It’s a bit like The War of The Worlds, isn’t it? You know, the martians were fucked as soon as they landed – it was just a matter of time. That’s the hippies for you.

In a way, Hippy was a great idea – sunshine, drugs, groovy cats and chicks getting into each others’ knickers because the pill meant you could do that without having babies, groovy music, wild colours and clothes, psychedelic light shows, bands with idealistic songs and great harmonies, recorded beautifully. You know, what could possibly go wrong?

Well, as always, what could go wrong, did go wrong, and what that was, was what I’ve just been talking about, which can be neatly encapsulated by Woody Allen’s line about how “The lion will lay down with the lamb, but the lamb won’t get much sleep.” Or, even older than that, “The meek will inherit the Earth. When the strong let them.”

And, like the martians in War of The Worlds, it was never going to work even before the breadheads and dickheads muscled their way in because the hippies weren’t even really about peace and love because they were into fashionable trousers, getting stoned, talking crap, and having sex with naive girls, as opposed to the hi-faluting ideals many of them talked about. Like Wooden Ships, you know? On the surface it sounds like a vision of the grooviest of all possible world, but actually, it’s a self absorbed power grab that involves everyone who’s not into your trip being dead.

By about 1988, Hippy was back, and exactly the same thing happened, in more or less exactly the same timeframe – two or three years. Summer 1967 was peak hippy, by the end of 1969, it had been taken over by cocaine and gun wielding psychopaths. Summer 1988 was the Second Summer of Love, and it was ecstasy and peace and love and dancing and flared trousers. By 1991, the gangsters had taken over The Hacienda and people were getting shot over drug territories.

Funny business, isn’t it? Like the old quote about “He who fails to learn from history is doomed to repeat it“. It was exactly the same thing.

In a funny way, I suppose my mother had the right idea, albeit at the wrong time: the only good things that came out of the Hippy era were the superficial things – the clothes and some of the music, providing you could forget about the naïveté of the proponents of it, which wasn’t that easy, on account of them being a set of self-absorbed, sanctimonious arseholes.

I suppose that flower power tie and that flower power pencil case I hated so much were, in a way, about the least offensive aspects of the hippy era. I didn’t know it then, but it all turned out the opposite way around for me in a funny sort of way.

I started off hating the ephemera of Hippiedom – the clothes, the patterns, the drugs, and the music – and being entirely ignorant about what it meant – self-absorption, sanctimony and stupidity. And I ended up loving the ephemera of it – the clothes, the patterns, the drugs, and the music – and hating what it meant – the self-absorption, sanctimony and stupidity.

And even though all that’s still pretty much true – most of it – there’s a part of me that feels about Hippiedom the same way that I feel about art in general: a lot of great art is made by dreadful people. Like Crosby, Stills and Nash. Honestly, what an absolute set of cunts. And what a beautiful sound they made.

And that’s how it goes, isn’t it?