“I opened the door to the psychedelic revolution.” Donovan.

In 1965, Donovan had exploded onto the music scene, and not just in Britain either. Catch The Wind, his debut single reached number 4 in Britain and number 23 on the Billboard charts in America. He was 18 years old.

His first two albums and the singles and EPs – both 1965 – were put together with his manager. By the end of 1965, he’d met and signed up with Ashley Kozac who introduced him to Allen Klein, who would manage The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, and complicated his business arrangements to the extent that, for years, if you wanted to buy a Donovan compilation that included his acoustic and psychedelic years, you had to buy two separate ones because of some complicated dealings that I don’t really understand or care about too much.

By 1966, Allen Klein had introduced Donovan to Mickie Most, a producer with golden ears whose productions for Donovan are a looking glass, through which it’s possible, in the 21st century, to understand what being a hippy must’ve been like in England, in the 1960s.

Sunshine Superman

Donovan recorded his first album with Mickie Most, including this, the title track, in 1965. What it is folks, is psychedelic. That’s right, it’s 1965 and it’s psychedelic. Even though Donovan never seems to tire of making claims that he invented pretty much everything that’s any good – and some things that nobody with any sense would want to be responsible for – in this instance, there’s not much doubt that he really was first down the rabbit hole. You might make the argument – and I certainly would – that as The Byrds were recording a single – Eight Miles High – that was at least as out there as Sunshine Superman at the same time in America. Donovan’s psychedelic excursions came from Indian music and Jazz. The Byrds were coming from exactly the same places. Sort of. Donovan’s Indian influences meant that he’d have sitars and Indian percussion on his records while The Byrds didn’t actually use authentic instrumentation but manipulated 12 string electric guitars in order to replicate the drones that the sitars, the sarod and the sarangi provided in traditional Indian music. Donovan’s jazzy side came through John Cameron who certainly worked with and around Indian sounds, but The Byrds were coming from John Coltrane’s modal experiments. Again, Donovan records featured saxophones and trumpets and The Byrds’ – generally – didn’t.

Unusually for a first, it’s fully formed and it’s outstanding. In part 1 of the Donovan posts, I mentioned that a lot of artists covered a lot of Donovan songs and this one is one of the most popular, at least in terms of cover versions. There’s nothing very complicated about the chords but the backing is extraordinarily well organised, unusual, and shows that Mickie Most was Donovan’s George Martin.

Starting off with two basses playing not so much in unison as sympathetically along broadly the same lines, the intent is there from the first couple of seconds. You’ve not heard records like this before, even if you’re familiar with the lyrical concept, which is “I fancy that girl and I’m going to get her to go out with me.” Which isn’t all that psychedelic, certainly it’s no Tomorrow Never Knows or Echoes, but it has enough nods towards methods of psychedelicising yourself for anybody hip enough to get it.

The basses – the electric one played by John Paul Jones, later of Led Zeppelin – are joined by Donovan’s acoustic guitar, congas, a cleanish electric guitar provides swells through Jimmy Page’s foot on a volume pedal (meaning this record contains 50% of Led Zeppelin and it’s still great, despite that) and, perhaps most significantly, a harpsichord, played by John Cameron, a noted arranger who worked extensively with Donovan but also provided a bucolic and incongruous soundtrack to Ken Loach’s outstanding Kes.

John Cameron’s contribution shouldn’t be underestimated on this and throughout Donovan’s classic psychedelic flower child recordings because, really, it’s the arrangements coupled with the lyrical content that psychedelicises Donovan’s output from here on.

Sunny Goodge Street was bordering on Trad. Jazz but this is another kettle of fish entirely. It’s jazzy alright, but through the filter of baroque beat music which didn’t yet exist. At all. Donovan, never one to knowingly undersell himself, describes Sunshine Superman at times as Latin Jazz, but he retains a tendency to call everything he does Celtic Rock. I’ll be honest, I don’t really know what Celtic Rock is but I’m prepared to stick my neck out far enough to say that, whatever it is, it’s not this.

Donovan is the eponymous Sunshine Superman and, let’s not faff about here, the reason is because he’s tripping his tits off ((Orange) Sunshine being a type of LSD) and making his mind up that he’s going to get this girl. This girl is, sweetly enough, the woman he ended up marrying at the end of the 1960s, more or less at the point at which he stopped making great records and drifted from delicate whimsy into the twee pixie persona that he remains as today. Does that mean that his psychedelic output was only any good because he had something to write about and somebody to impress? I wouldn’t go quite that far, but I think there’s certainly an argument to be made that not getting what you want leads to better art than comfortable complacency. Maybe it’s a coincidence…

Having recorded the entire album that would become Sunshine Superman, the contractual issues between his original managers, Ashley Kozacs, Allen Klein, Pye Records and Epic Records really bit him on the backside.

The modus operandi for Donovan records for the next year would be this: Donovan wrote the songs, Mickie Most made suggestions about possible arrangements which John Cameron then worked on. Donovan plus various session musicians recorded them under the guidance of Mickie Most and then Donovan’s first two managers and Pye Records issued writs that prevented the records from being put out in the UK, leading to court cases which would eventually result in Donovan being allowed to release them after all, but in the fast moving mid 1960s, the times and Donovan had usually moved on by then and a new record was ready to be released but wouldn’t be (at least in Britain) because when the release date approached, his first managers would issue a writ against the new material again. And so it went on.

The first time this happened was with the single of Sunshine Superman in late 1965 which was blocked from release. On hearing the news of this, Donovan decided that the game was probably up: he’d had it. His records would never get released because of his complicated contractual situation and he buggered off to the Greek island of Paros with his ever present mate, Gypsy Dave but without any hope of putting any records out again.

A couple of months down the line, Kozacs finally got hold of Donovan (on, allegedly, the one and only existent telephone on the island) and told him that Sunshine Superman had been released in America and was currently sitting pretty in the top spot and he should get his arse back to somewhere that had more than one telephone in order to promote it further.

Sunshine Superman had been released in around July 1966 in America but wouldn’t be available until December 1966 in Britain. Its identically named parent album suffered a similar but worse fate. It was put out in America in September 1966 but – get this – wouldn’t be released at all in Britain.

As pop groups tended to put out two albums a year at that point, Donovan was being pressured to write and record material for the follow up album, which he did and, surprise, surprise, that one didn’t get put out in Britain either.

By the time Donovan had recorded what would become the Mellow Yellow album, the Sunshine Superman album had gone through the courts and that could have been released in Britain but Pye, in their infinite wisdom decided not to bother and put together a compilation of tracks from both of these albums and released them, with the same cover as the American Sunshine Superman album, as Sunshine Superman. When this single was finally released in Britain, one whole year after it was recorded, it was still seen as groundbreaking and reached number 2. The Beatles’ Revolver was a December 1966 release and, if not exactly their first attempt at psychedelia, was truly groundbreaking. Donovan had been getting trippy 12 months prior to The Fabs. Yeah. Dig that vibration, baby.

Some people got Donovan’s American albums though, not least The Beatles, in whose film of the A Day In The Life orchestrations taking place in front of the glitterati of Swinging London, the American Album of Sunshine Superman can be seen rotating on a record player in the studio. The Beatles were into Donovan and he never let anybody forget that. And why would he, I suppose? Perhaps he brought a copy to the session and, like Oasis would thirty years later, decided to play his own records at parties.

And it wasn’t just The Beatles who admired Donovan. There are stacks of covers of Sunshine Superman out there, from the Garage rock stylings of The Standells to the easy listening jazz guitar vibes of Gabor Szabo, to the scatting jibber-jabber of Paul Jost to the abrasive noise of Husker Du, to the Hammond organ a-go-go of Soul Survival, to Trini Lopez’s early mashup of it with The Box Tops’ Cry Like A Baby, Sunshine Superman was a money making dream come true.

That’s to get ahead of myself though. I’m going to be looking at his records purely in terms of his American releases.

Season of The Witch

If Sunshine Superman is an evergreen summertime smash – and it pretty much is – then Season of The Witch is a Hallowe’en classic of creeping malevolence, not something you’d generally associate with Flower Children, but then, Donovan’s not making any claims for his own devilry, he’s describing other people’s.

Like Sunshine Superman, this is another two chord vamp with a third chord getting introduced in the chorus. Unlike Sunshine Superman, Season of The Witch‘s chords are slightly more complicated, if not by much. Sunshine Superman mainly takes place over C7, with brief excursions to F and G7 in the chorus – all pretty straightforward chords and ideal for people who’ve not been playing the guitar for very long, such as kids in garage bands. C-F-G is, to get slightly technical, is a I-IV-V progression, which is about as basic as it gets. Season of The Witch is A, briefly nipping to an A7, to a D7, but with F# in the bass and the high ‘e’ string open. The dah-dah-dah part over the A chord is the brief nipping to A7 and I don’t know what you call it on the D7-ish chord, but you do it by lifting your first finger from the C note on the B string and letting that ring for the dah-dah-dah part over that. Like Sunshine Superman‘s brief wander to the V chord (G7 in that case), Season of The Witch also pops over to its V chord (E in this case) in the chorus. Both songs are, basically, I-IV-V – the most straightforward chord changes in pop music, even if whatever the fancy name for the D7 with an F# in the bass and the emphasising B note makes it slightly more complicated than Sunshine Superman, it’s hardly jazz. Even the fancy sounding guitar fill that crops up repeatedly after the second verse is nothing more complicated than a bit of dribbling over that fancy arsed D7 with an F# in the bass chord – you barely have to move your fingers to get it.

In fact, if Sunshine Superman was pretty jazzy in a Latino sort of way, Season of The Witch is pretty fucking far from jazz. The straightforwardness of the chords of Sunshine Superman made it a pretty popular choice for amateur garage bands – because it doesn’t have to be jazzy – but Season of The Witch was probably in every single 1960’s garage band’s repertoire, especially as the two chord vamp made it easy to drag out and extend with noodlesome soloing from guitarists and Vox continental organ players from New York to Los Angeles.

And, by God, have they. None more so than Al Kooper and Stephen Stills on the Super Session album of 1968, who noodle around for over 11 minutes of it. Horns were overdubbed later on this version of it and, frankly, I don’t like them at all. What I do like is Stephen Still’s wah-wah guitar and the version that came out a few years ago without the horns. I like Stephen Stills. I say I like Stephen Stills, but I don’t really. Well, no, I do like him: I think he wrote some fantastic songs, I think he was a superbly inventive guitar player and an excellent singer, but I also find he comes over as a bit of a dickhead. I’ve been writing about Crosby, Stills, Nash (And Young) and haven’t finished that yet, so I won’t go into him here.

There are one hell of a lot of covers of it out there and, in addition to the Super Session version (without horns, ideally), I particularly enjoy Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & Trinity’s similarly elongated version. The video below, replete with all the trimmings of mid-late 60s England, is a particular delight. In fact, it’s my favourite version, including Donovan’s.

If the chords of the two big songs on the Sunshine Superman album aren’t a million miles away from one another, neither is some of the imagery. The first lines of both songs deal with windows. Sunshine coming in on the first one, Donovan looking out of one on the second. Did they have windowpane acid in 1966? I don’t know. Maybe. Both sets of lyrics work because they’re vague enough to read whatever you want into them, Sunshine Superman’s are pleasant and optimistic, Season of The Witch’s evoke paranoia and pessimism, neither of them making the mistake of going into the sort of detail that could prevent anyone from reading their own interpretation into it. “You’ve got to pick up every stitch...” What’s he getting at there? I suspect he’s just found a rhyme for “witch“, but it works because you could read anything into it. At least, anything relating to making sure you’re not overlooking something that could allow these witches in to cast spells on you. It’s paranoid – meticulously poring over everything and everyone to make sure they’re not going to get you.

When I saw Donovan in 1990 and he played this song, he changed the lyrics from, “Beatniks are out to make it rich...” to “Yuppies are out to make it rich…“, as if to emphasise that his essential message was just the same as it always was – watch out for the breadheads, man. I’ve not seen him live since and have no desire to either, but I would be surprised if “Beatniks” hadn’t changed from “Yuppies” to “Hipsters” by now.

If Donovan has one stone cold classic in his catalogue, it’s probably Season of The Witch. And it’s fucking great, isn’t it? It is, and it’s also pretty unrepresentative of how he’s viewed – paranoid, twitchy and scared. It’s hardly synonymous with Flower Power, is it? What does that mean? It means that Donovan’s image – even the one he tries to emphasise – is at odds with, possibly, his most enduring song.

The rest of the songs on Sunshine Superman don’t really live up to the two I’ve written about in terms of immediate impact or longevity and, really, the remainder are the bridge between his acoustic troubadour persona of 1965 to his Flower Child schtick. John Cameron’s arrangements are the difference – and Mickie Most’s production and recording too. There are sitars and other, non-beat group instruments all over it. Some of the songs go on a bit – I’m looking at you, Legend of A Girl Child Linda – but there’s enough of interest to elevate it well above most other albums of late 1965 – early 1966. There’re gently orchestrated folky guitar songs (Guinevere, Legend of A Girl Child Linda), Indian drones (Three Kingfishers, Ferris Wheel, The Fat Angel (about Mama Cass)), further jazzy excursions (Bert’s Blues (about Bert Jansch, who showed Donovan a fair bit on the guitar), Celeste, which is just lovely), groovy depictions of Swinging London (The Trip).

As a snapshot of Swinging London and where it was headed, you can’t do much better than Sunshine Superman, the album, although I’m going to stick my neck out and suggest that what would come next would surpass even this, in terms of everything.

Mellow Yellow

If Season of The Witch is Donovan’s coolest record then Mellow Yellow is probably his most famous, as it says in the chorus – quite rightly. Sunshine Superman was spaced out, Season of The Witch was ominous and Mellow Yellow has its tongue planted right in its cheek all the way through it. You could say a lot of horrible things about Mellow Yellow, if you felt so inclined, but none of those things would include “ominous” or “paranoid”.

Starting off with crisply struck, closed hi-hats and tight sounding drums that don’t sound so much mellow as twitchy – but not in a bad way – Mellow Yellow doesn’t appear to have any acoustic guitar on it at all. There’s a wooly sounding electric guitar and bass most of the way through it, joined by a brass section that provides a fanfare for the farcically laid back Donovan to sing about how mad he is about Saffron and a girl called fourteen. Whether fourteen is actually fourteen years old is possibly a moot point in this day and age, as well it might be but, as Donovan’s Flower Child persona doesn’t exactly radiate potentially threatening sexuality, maybe he got a pass. Mind you, who didn’t in the sixties? When The Beatles sang, “I want to hold your hand...”, the underlying feeling was that they wanted to do rather more than that. Had Donovan sung that, I expect he’d have meant exactly that. Take Turquoise’s most gentle line, “Take my hand and hold it, as you would a flower.” Maybe when he said “hand“, he meant his willy or something, but I’d be surprised.

‘Saffron’ would have been a pretty unusual name at that point too although you did come across Saffys when I was growing up. The girl I knew from Morecambe at university had a friend called Saffron who came up to visit and she wasn’t keen on being called Saffron and, when I asked her if her parents had been into Donovan, she told me they had been, much to her consternation. I thought it was a shame because I like Saffy as a name and, obviously, I’m into Donovan, as I was then. That Saffron also told me that her auntie knew someone from Ian Brown’s family (The Stone Roses) – this was during their hiatus of recording Second Coming and no news was forthcoming in the press about them – and she said that her mum’s friend had told her that Ian had spent all the record company money as soon as he got it. As that was the total extent of the information I learned about them while they were away, I made do with it. Anyway, I digress. For a change.

The lyrics are, unusually for Donovan, extremely straightforward, repetitious and to the point. Well, most of them are. He’s mad about ‘x’ and she’s just mad about him. And so on. However, the last verse developed a certain notoriety.

“Electrical banana

Is gonna be a sudden craze

Electrical banana

Is bound to be the very next phase.”

For reasons that are beyond me, some people interpreted that as meaning that you could smoke banana skins in order to get high. Why they thought that, I don’t know. Electrical banana? Having looked it up, Donovan claims (Donovan’s claims should always be taken with a pinch of salt) that the rumour started with Country Joe (who was on at Woodstock and fitted right in with that crowd of divvies, if you ask me). Big deal, huh? Donovan’s explanation makes more sense although, as usual, maybe we should be skeptical about explanations of anything from Donovan’s lips. Donovan says that it’s about vibrators, which at least has a go at explaining the electrical element as well as the phallic side of those particular berries. Is it? I don’t know. Maybe. Big deal, I suppose. Maybe he was a pervert after all.

By this point, Donovan was firmly in with The Beatles, having contributed the line, “Sky of blue, sea of green,” to Yellow Submarine in 1966 as Paul McCartney was writing it. Macca returns the favour here by joining in with the sing along at the end. People have claimed that it’s him singing “Quite rightly” but it obviously isn’t because it’s Donovan and Donovan sounds nothing like Macca. Even so, Macca’s not just joining in with the cries of ‘Mellow Yellow‘, he’s the one whooping along and singing the word ‘yellow‘ in a strange voice at about 2:17 on the record.

I have to say, I don’t love it but even a miserable old twat like me can’t deny that, as a jaunty, good time sing along from the psychedelic era, it’s hard to imagine how it could have been any better.

Mellow Yellow, despite being another massive hit for Donovan didn’t spark as many cover versions as his two big hits from Sunshine Superman did. My favourite one is a reggae tinted version from 1969 by the Bread & Beer Band, on The Beatles’ Apple Records, featuring a pre-fame Elton John. It’s largely instrumental although the notes on the video I’ve linked to say that you can hear Elton John’s ‘unmistakable’ vocals on the chorus but I can’t. I like the picture on the cover too.

Writer In The Sun could have slotted comfortably alongside anything on Sunshine Superman, the laid back jazz backing illustrating the somnambulance that he must have felt when he’d thought that his pop star days were over. It’s slight but pretty, which was fine in 1967 but ten years later would be a definite no-no.

Sand & Foam

In a lot of ways, Sand & Foam could have appeared on Donovan’s first two albums. It’s just him and his acoustic guitar, Travis picked. Travis picking is a fingerpicking pattern that Donovan never tires of telling anybody who’ll listen that he taught to John Lennon in Rishikesh, India during their stay at the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Ashram on the banks of the Ganges. Paul and George didn’t bother learning it but, as George said, “Donovan’s all over (The Beatles’) White Album.” Which means that Lennon Travis Picked on quite a few of the songs that appeared on it, most notably Dear Prudence and Julia, but also the opening section of Happiness Is A Warm Gun and Look At Me, which didn’t appear on The White Album, but was written at the time. It’s not like Donovan invented it, he was taught it by Mac McLeod who later formed a band called Hurdy Gurdy, for whom Donovan wrote Hurdy Gurdy Man but was persuaded not to give to them by Mickie Most, but that’ll come later. If you play the guitar, I strongly recommend learning how to Travis pick, it takes a while to get get your fingers going but once you’ve got it, you can do all sorts with it and playing Dear Prudence properly is a joy. And, if you’re into that sort of thing – and most guitar players are – if you can play Dear Prudence properly, people are always dead impressed. Well, people who enjoy listening to people playing the guitar at parties which, let’s not pretend otherwise, isn’t everybody. Wait until someone shoves a guitar in your hand and asks you is my advice. Don’t instigate it. And don’t play Wonderwall if it does happen, even if someone asks you to.

The lyrics show again that Donovan had a poetic turn of phrase. “The sun was going down behind a tattooed tree,” is a great opening line. Similarly, “Grasshoppers creaking in the velvet jungle night,” more than does the job economically without being gauche. I’m not saying he’s a poet, but I am saying it’s not all, “Hello trees, hello sky,” hippy-dippy platitudes, even though he is singing about trees and the sky, he does it poetically at least.

It’s simple and it’s evocative. What more do you want?

Julie Felix, who had a television programme, covered this under its original title Mexico and I quite like it. It’s a lot jauntier than Donovan’s. If anything, it sounds like a cowboy version of it which probably works with the title of Mexico.

The Observation and Bleak City Blues hark back to the straightish jazz of Sunny Goodge Street but without half its charm and I don’t have anything to say about either of them. Eminently skippable.

House of Jansch, like Sand & Foam, is back to his acoustic Troubadour phase – with a bit of instrumental punctuation along for the ride – and, like Sand & Foam, shows that Donovan was really good at it. Jansch is Bert Jansch, one of the big folk guitar players of the day – and any day – I’m a big fan of his. Still, it’s fairly slight, as is Young Girl Blues which follows it.

Museum was covered pretty much straight by Herman’s Hermits and is another of his Swinging London jaunty travelogues. “Meet me under the whale at the Natural History museum” sets the location and melodically the hook of “Yawning in the sun, like a child I run,” finds Donovan plagiarising himself and not for the last time either. The melody of that couplet is, melodically, very close to “When you’ve made your mind up you’re going to be mine,” from Sunshine Superman.

The final Swinging London travelogue on this album is also the best one: Sunny South Kensington. It’s perky and very much redolent of the era it describes, which is perfect. It’s no single, but it has a good go at immediacy.

Referencing French film star Jean Paul Belmondo (Pierrot Le Fou is a continuing source of delight to me from beginning to end, I strongly recommend it) and Mary Quant getting “Stoned to say the least...” it’s jaunty, like Donovan’s Swinging London songs tended to be. There’s not much to say about it except that it might be yet another example of how Donovan was already beginning to run out of ideas. The stabbed harpsichord and periodic breakdowns yet again bring to mind Sunshine Superman. Maybe it was Mickie Most not fucking with the formula but either way, by this point, there are definite signs that Donovan has a limited palette from which he was working: Acoustic troubadour songs with poetic imagery; jauntily rhythmic Swinging London travelogues with stabbing harpsichords, and jazz inflected slower songs. In fairness to Donovan, he’d expand into children’s songs very shortly while not leaving any of these three styles too far behind. It seems slightly odd to me that he didn’t pursue his hippy paranoia garage band style of Season Of The Witch beyond that one song though. Perhaps he’d said all he had to say about that on that one song. Still, that sort of self-awareness didn’t seem to apply to his other, commonly repeated styles, so who knows?

Hampstead Incident, like Sand & Foam, Writer In The Sun and Bleak City Blues, is evidence that Donovan wasn’t just Mr Positivity Flower Child by this point and it’s yet another slowish jazz track that tries and fails to reach the heights he set for himself with Sunny Goodge Street.

Epistle To Dippy

A stand alone single from 1967 about a school friend who’d joined the army that was only released in America, Epistle To Dippy. It’s, yet again, light as air and features musical elements that have worked for Donovan before. This time, primarily the volume pedal on the guitar and harpsichord (again, both from Sunshine Superman), again played by Jimmy Page. It stomps along, dragging the string section with it, breaking down for the clanging bridge sections, similarly to Sunny South Kensington. Donovan eats himself, I suppose but it’s done with charm and his vocal performance is full of enthusiasm and character.

It’s wobbly and sloppy – more drunk than stoned, if you ask me – but great nonetheless.

Having been made aware that there were going to be issues with album releases, if not quite so much with singles, Donovan appeared to accept this and adapted to it. The songs that appear on the album Mellow Yellow continue his path from Sunshine Superman but only Mellow Yellow (the song and single: number 2 in America, number 8 in Britain) appears on the album. Also released around this time were Epistle To Dippy (number 19 in America, not released in Britain) and There Is A Mountain (number 11 in America, number 8 in Britain). Both of them are fantastic. Jim Morrison of The Doors, on hearing Epistle To Dippy, pronounced it “Stoned immaculate.” Not that Jim Morrison’s words should be taken as great pronouncements, but he was a big deal in the hippy world – even if he, too, dealt largely in terms of the darker side of hippydom, like Season of The Witch did.

There Is A Mountain

There Is A Mountain, which I don’t doubt made Primary School teachers with acoustic guitars behind their desks salivate – and good on ’em, is the sort of thing that people who like to sneer at hippies also lap up, although in an entirely different way to groovy primary school teachers of the early 1970s. Well, fuck them and the horse they rode in on because it’s great.

Here I am, being slightly snarky about primary school teachers who got kids to sing songs in the round and I’m no better. Given half the chance, with year 7 kids, I divide them up and get them singing Frere Jacques in the round too. I’m into it, so shoot me, eh? If they knew There Is A Mountain, or Happiness Runs by Donovan, I’d get them doing that too. First against the wall, come the revolution, that’ll be me…

A Gift From A Flower To A Garden – The Zenith/Nadir of Hippy.

As a man who has no concerns whatsoever about proclaiming my love for most – if not quite all – things Donovan, it may come as no surprise that I’m not the most masculine man in the world. I don’t mean I’m going out with Lola from The Kinks’ record, but I do mean I have a soft spot for the hippy ideals, even if I don’t actually want to be one. Or meet anybody else who is one. What this means is that I’m prepared to listen to some records that most people would consider very bad indeed.

In terms of Donovan, that statement might encompass pretty much everything I’ve already written about, but I’ll happily argue that people who turn their noses up at, say Sunshine Superman, are just daft. On the other hand, if the world’s Donovan naysayers were to smack me in the chops with this boxset, I might be inclined to cringe a bit and suggest that they might have a point, even though there are some lovely songs in it. A couple. At a push. Still, I quite like some of the twaddle too.

Before we even get to thinking about the sounds on the records, it would be a shame not to spend a couple of minutes looking at the thing itself which, in itself, is a strange thing.

First things first – what does the title mean? The “Gift” is the boxset of records, the “Flower” is Donovan himself – of course it fucking is – and “The Garden” is the world. Beautiful? Oh, God, yeah. Vomit inducing? Oh, God, yeah.

It’s (only) a double album, meaning that it doesn’t really need a box to hold it, although it came after Blonde On Blonde (The Dylan double album of June 1966) in December 1967 in America (April 1968 in Britain). I’m not Mister Rock History or anything, but it might have been the first box set by a pop star. Certainly it came before George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass box, which was a triple album, even if nobody in their right mind has ever listened to the third record in it all the way through.

As we approach it, it starts well and goes downhill rapidly and consistently from there. The front cover’s infrared photography of him holding some sort of peacock feather lollipop and lovebeads while dressed in a kaftan is about as lysergic as still photography gets. I’m into that. The back cover has Donovan sitting with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, of The Beatles’ association fame.

Opening it up, there’s the records, a textured wallet holding coloured watermarked sheets with the lyrics for the second album’s songs printed on it, along with black and white illustrations that are very much in line with children’s Nursery Rhyme books of the era. I used to have one that my Auntie Val gave me, and I fucking loved the pictures in that. Proust had his lemon cakes and I had that book, which I’ve now lost and can’t find it – which regularly disappoints me. I’ll find it one day. I can’t even remember what it was called. Bastard.

There’s also a sheet pasted onto the inside covers of the actual box. The one on the back is the same cover used for the album “Wear Your Love Like Heaven” (linked above – and it’s gentle as anything), featuring Donovan in a coracle in the moat of Bodiam Castle, where his short film with Jenny (Juniper) Boyd (sister of Pattie Boyd, wife of George Harrison) was filmed. Both records were released separately in America. But it’s the sheet pasted inside the front cover that’s my favourite.

The main body of the text comprises the lyrics to the first album, referred to here as, “Phonograph Record/The First”

To the left of that is an introduction that Donovan’s written that I shan’t print here, but the gist of it is that the first record’s for the groovy grown ups and the second one (Phonograph Record/The Second) is “For The Little Ones”. Which, I have to say, despite myself, I find a beautiful concept. Donovan doesn’t say that in so many words because he says, “To these dear “little ones” I bequeath the second phonograph record.” That’s right, he bequeaths it. Of course he does, the great pansy.

He goes on – at length – to suggest that, with their bequeathed phonograph record, “No child shall be lonely“, which is sweet – beautiful even. I mean, it’s a bit optimistic, but I dig it. Maybe it was guilt due to the fact that he’d had a child – Donovan jr, natch – whose mother he’d pretty much abandoned because she didn’t want the life Donovan was into, hence he didn’t see too much of Donovan jr. Guilt? I expect so.

It gets even better though, “I call upon every youth to stop the use of all Drugs and banish them into the dark and dismal places. For they are crippling our blessed growth. Yes, I call on every youth to stop the use of all drugs and heed the Quest to seek the Sun.” (bold text and capital letters: Donovan’s).

He signs off – “Thy humble minstrel” and adds a postscript, “One need only look at our frustrated youth to see the fantastic amount of misdirected energy.”

I don’t really know what was going on his mind at that point, especially considering that his target audience would have needed to imbibe one hell of a lot of drugs to get through what he was laying on them at this point. Especially considering his prosecution for possession of pot and his association with that and acid. Maybe that was it – aiming to throw the law off the scent (of patchouli and lord knows what else) by pre-empting it with this. Who knows? The word at the time was that Maharishi had encouraged Donovan and The Fabs to give up bad drugs and go for meditation instead which might have worked for a bit, but evidently not very long, at least in the case of The Beatles. Donovan denies this in his autobiography, saying, “...I had come to this decision completely on my own – I was not asked by my guru to drop drugs… I still believed that the soft drugs cannabis and magic mushrooms were far safer than alcohol and tobacco.” Which isn’t entirely consistent with his proclamation on this set’s sleevenotes. Perhaps he wanted to say that they should give up booze and fags and start tripping on mushrooms and smoking pot instead but The Man wouldn’t let him, or something. Again, who knows?

All that, and we’ve not even got to the point of listening to the records which, frankly, are a bit turgid.

It starts off nicely enough with Wear Your Love Like Heaven, which is lovely. Produced again by Mickie Most, it’s a run through the colours in his painting box and references to Allah kissing him, Lord this and Lord that and, it’s generally a hippy dribbling about cosmic love – and it’s better than it sounds. Unfortunately, this and its corresponding b-side (Oh Gosh) are the only songs produced by Mickie Most on the whole double album, Donovan taking over duties, although Most is credited for the lot. Donovan seems quite proud of that, but it seems like a mistake to me. Most’s production was always sympathetic and inventive. Modern, with an eye on a half imagined medieval past. Donovan’s production sounded like a children’s television programme’s idea of a groovy three piece jazz outfit – cheesy keyboards, string bass and Donovan on guitar and vocals. The arrangements were always relatively varied throughout the previous electric albums – at least to the extent of the three main types I mentioned earlier – this was a one-trick pony. A trick that was bordering on lift muzak a lot of the time.

The second album harked back to Donovan’s acoustic era – 1965 – and featured children’s songs, mainly of the nursery rhyme variety. It’s okay, but I’m not going to pretend I listen to it much – if at all these days. Which isn’t to suggest that children’s records aren’t my cup of tea, because some of them very much are. I’ve previously mentioned how The Velvet Underground could have – should have – put out an album of children’s songs

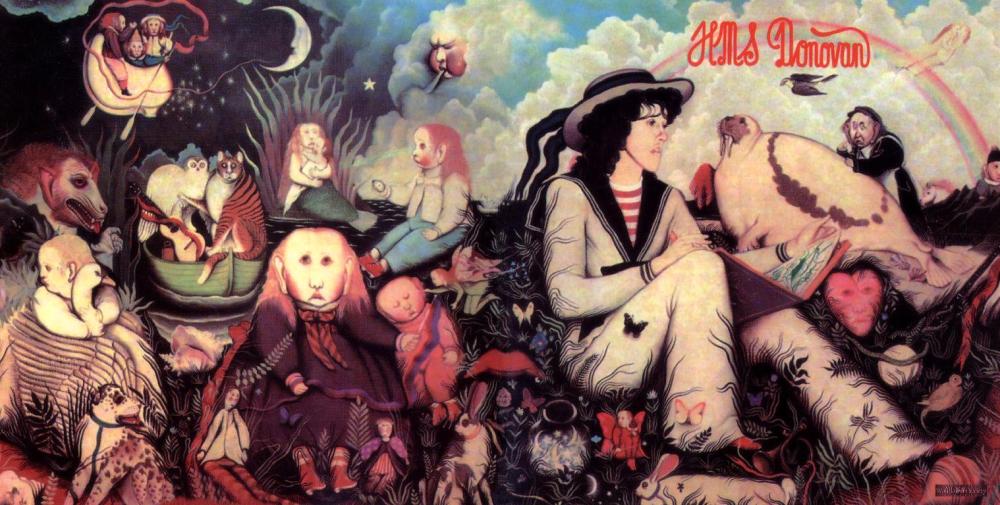

A couple of years later, Donovan put out an entire double album of children’s songs (HMS Donovan) and that’s a lot better than everything on this boxset, except Wear Your Love Like Heaven, which is great.

Some of the songs on the first album are just woefully fey. In fact, almost all of them are wetter than a haddock’s bathing costume. Quite apart from the uninspiring musical backing, some of the lyrics, even by Donovan’s standards, are practically begging for punk to come along and burn them to the ground. And then pour salt on what’s left to prevent it ever growing again. Brothers and sisters, I give you…

“Flowerpot on windowsill / on top of honeycomb hill.”

“With your coat of many colours / and the flowers in your hair / you may love away pleasant hours / to think upon all that is / fair to look upon and to touch / Oh gosh, life is really too much.”

“A little boy in corduroy / a little girl in lace / a little boy jump for joy / colour in a space”

“Happy I yam (sic) / all on a new day / happy I yam / people and flowers / are one and the same / all in a chain / at the beginning of a new world / someone’s singing and I think it’s me.”

Just shit. Namby pamby drivel, isn’t it? Too much? Yes, Don. Much too much.

Next step for Donovan, bringing out a live album, Donovan In Concert, the best bit of which is the introduction about “The Phenomenon Of Donovan” that I quoted at the top of Part 1 of this essay on him. I’m not going into it here at all, but I will say that his band at the time were pretty much based on his band for “A Gift From A Flower To A Garden”, which means it was a bit cack.

The Hurdy Gurdy Man

Following his visit to Rishikesh, India with The Beatles to meditate and get groovy with the Maharishi in spring 1968, Donovan, like the Fabs, came back with a stack of songs that he’d had time to write, in between teaching John Lennon how to play Travis fingerpicking – has he mentioned that? N.b: sarcasm. On the plus side, Mickie Most was back.

Unlike The Beatles’ songs from that time, Donovan incorporated a fair bit of Indian influence into a couple of them – and made a pretty good job of it, too. The Beatles, of course, had had their Indian influenced phase already, from Norwegian Wood (1965) up to Sgt. Pepper (1967), with only the odd little excursion back, and even that was recorded before they went to India (The Inner Light, 1968).

Peregrine is mainly tambura, droning all the way through it. It’s not great, Donovan’s equivalent of The Beatles’ Blue Jay Way, which is nobody’s idea of a good time. The Entertaining of A Shy Girl is another of his acoustic guitar songs, but with a cello providing the Indian-esque drone and a flute flutters around endearingly, like one of the birds who helps Snow White fold the washing. Other acoustic songs aim for something bordering on slightly spooky, but nothing approaching Season of The Witch – The River Song, and Tangier, both with Indian accents. Bert Jansch plays on Tangiers and I like him a lot, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it- Donovan’s a very good guitar player, even if he’s not Bert Jansch. The worst thing you could say about some of these is that they’re a bit slight which, following A Gift From A Flower To A Garden, sounds worrying, but actually they sound like bulldozers made out of Sherman tanks in comparison with most of that. As I Recall It is jazzy, but more like the jazzy wobble of Mellow Yellow than the lift music crud of AGFAFTAG.

Apart from the Indian musical instruments dotted around, the other startling thing about this record is the drumming which, at times, is funky as hell. And beautifully recorded. Get Thy Bearings is the main one. The saxophone – which I’m not really a fan of on pop records – isn’t too bad as these things go, but the drums, man. Pfff. Fatback drums like that were ripe for sampling in the 1990s, and Biz Markie helped himself to them – and Donovan’s singing of the hook on his less than seminal I Need A Haircut album of 1991. Showing a marked lack of originality, Finsta Bundy sampled Biz Markie’s sample on his Crush from 1994. Oddly enough, on the French Hip Hop single, Les Sages Poetes De La Rue, Bouge Tete Seuf sampled Donovan’s hook but not the drums. For a drumbreak that sounds fantastic by itself, I find it mildly odd that Donovan’s voice is almost always sampled along with them. There’re more examples than I’ve included on this little list, and no wonder. Apart from the singing, which does make me wonder…

The rest of the album comprises some proper crud, especially The Sun Is A Very Magic Fellow, which sounds as trite as the title implies.

What’s happened so far then? Since 1965, Donovan’s ditched his swinging London travelogue songs but gained twee children’s songs which are mainly acoustically presented, which means he’s lost some of his bite. Jazz inflected recordings are still here, although he’s gone from slightly oompah-ing New Orleans wobbling to Lift muzak jazz combos and back again. He’s dipped into Indian orchestration maybe three years after The Beatles started doing it and two years after it was a big thing – Paint It Black, Eight Miles High, Shapes Of Things To Come, etc.

In short, what’s happening is that Donovan has gone from being the cutting edge – even if people laughed at him a bit – to being someone chasing the zeitgeist.

Except for one song – The Hurdy Gurdy Man – an astonishing, if incongruous addition to his catalogue.

Written for Jimi Hendrix, Mickie Most wouldn’t let Donovan give it away, and he was right about that because it’s by far the best song on the album – and one of Donovan’s best. Thinking about it, it belies my earlier claim that Donovan didn’t pursue the paranoid inflected Season of The Witch style from 1965, because, if anything did, it’s this. Possibly Barabajagal too, which is his other great song from the late 1960s.

Unfortunately, Donovan likes to muddy the waters of this outstanding record by occasionally claiming that it’s him and Jimmy Page, John Bonham and John Paul Jones, who’d later form Led Zeppelin. It’s not. John Paul Jones plays the bass on it, but the drummer’s Clem Cattini, famous session man who played on hundreds of hit singles, and less famous session guitar player, Alan Parker. Jimmy Page claims he’s on it, and maybe he is, but it would appear that Parker, who also doesn’t get any credit for playing the riff on Bowie’s Rebel Rebel (Bowie claimed it was all him, which was apparently in response to a lot of people suggesting that Mick Ronson was the talent in The Spiders From Mars, which is daft – not that Ronson’s any slouch, but he needed Bowie more than Bowie needed him) would be the sort of guitar player that other guitar players like to pretend they actually are.

It’s all fantastic – the song, the drums, the guitar, the singing – which introduced Donovan’s auto-tremolo effect on his voice which blighted the rest of his career in a lot of ways. The guitar, in particular, sounds totally unhinged, like Parker’s pulling the strings off the neck with one hand and wrenching them to notes that didn’t previously exist, even though he wasn’t and they did. I’m not a big fan of heavy guitar playing at the best of times, but this performance is astonishing. Hats off.

The other way that Donovan makes this hard to listen to is when he goes on about how he invented Celtic Rock with this record. Whatever Celtic Rock is – and I think he means Led Zeppelin, even though I think of Celtic Rock as being Big Country, who made a career of having guitars that sounded like bagpipes – not a good thing. Led Zeppelin? Can’t be doing with them at all. Well, hardly at all.

It’s another big cover song. Steve Hillage did his droning hippy guitar thing for about twenty minutes that people like Neil out of The Young Ones would have lapped up. Later, in the early 90s, American Hardcore band Butthole Surfers covered it, and did it pretty straight – as most covers tend to be. It’s maybe not a great song, but it’s a great record, and that means the playing is shit hot – which means people like the sound of the record, rather than the song itself. Fair enough – it doesn’t get a lot better than this.

As such an evocative record, like Season of The Witch, it appears in a lot of films and television series. It was featured quite heavily in Zodiac – about serial killers, and Britania, the absolutely batshit British television series about Druids and The Roman invasion. Batshit, but none the worse for it. In fact, all the better for it.

Fun fact – There is no Hurdy Gurdy (musical instrument) on The Hurdy Gurdy Man, the drone is the tambura again, which you’ll have already heard on The Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever.

Speaking of Donovan’s voice, I’m of the belief that – around this time, or slightly later – he lost his singing voice. Listen to his earlier records and what came after this. The later material sounds like an impersonation to me. Maybe it was the fags or the pot, or something else, but whatever it was, Donovan lost it quite badly. That he’s managed to just about cover it up in the years since shows his craftsmanship, but he definitely lost his voice – as it was – in the late sixties, and it never came back.

Barabajagal

In some ways, The Hurdy Gurdy Man is to Donovan what Their Satanic Majesties Request by The Rolling Stones: an album by a popular artist that didn’t do very well at the time and is held up by hipster dudes and dudettes as being a lost treasure. I’m not averse to either of them, but Their Satanic Majesties has a couple of excellent tracks on it – 2000 Light Years From Home, She’s A Rainbow and a lot of dross. Hurdy Gurdy Man has one great song on it and one with a bit of funky drumming. Neither album is any hot shit.

Barabajagal is better than Hurdy Gurdy Man, but not by much. The title track – again – is great and there’s a lot of crap filling it up. Although, to be fair, there’s one other classic on it and the odd song that’s worth it. However, the really bad stuff is fucking appalling.

To cover the crap first – Where Is She? I Love My Shirt (as ironically covered by Trevor & Simon), The Love Song, Trudi, Pamela Jo. The Love Song has, possibly, the worst “party scene” interlude in the world and the rest are just nunty.

Better than those, but still not great is To Susan On The West Coast Waiting, which was a single about an American soldier in Vietnam who doesn’t want to be away from his girlfriend is – yet again – slight.

Which leaves the great and the good: Barabajagal, Superlungs My Supergirl, Happiness Runs and Atlantis. Not a great album, but a better hit rate than the previous three – or four, I suppose, albums of his.

Barabajagal (Love Is Hot) was the equivalent of Hurdy Gurdy Man, meaning, a heavy band with a loud guitar player. Jeff Beck was that man and, again, it’s a great job. Perhaps even better than his performance is Ronnie Wood’s – of all people – on bass. It’s probably a better song than Hurdy Gurdy Man, with a more defined and consequently repetitive guitar line, which allows the bass to go off and do its own thing. It’s not as lauded as Hurdy Gurdy Man, but it’s still a great, great record.

There are lots of covers of it too. Like Hurdy Gurdy Man, the covers tend to stick quite closely to Donovan’s arrangement, if easing slightly into Jazz. There are plenty on YouTube and you’ll get sick of them pretty quickly because they’re pretty much all the same.

Superlungs My Supergirl was originally recorded during the Sunshine Superman sessions in 1965 but not released. This is a re-recording and is tightened up quite significantly from that version. It sees the reappearance of “fourteen” from Mellow Yellow, she knows how to draw, apparently. The verb “draw”, of course, relates in this context to drawing smoke from a cigarette of some description – despite Donovan’s claim on AGFAFTAG about how drugz are bad. Man. It’s not up to Barabajagal, or Atlantis, but it’s not bad.

Happiness Runs is another children’s song for the primary school teachers I like to lightly mock despite, to all intents and purposes, being one myself. Graham Nash, Mike McCartney – brother of Macca – and Lesley Duncan sing backing on it – and it’s great. Lesley Duncan, incidentally, didn’t want to be a solo singer because of crippling stage fright, although she did release a few records, my favourite of which is Love Song, which appeared on the outstanding Folk Music compilation Gather In The Mushrooms, which I might write about one of these days.

Atlantis is, I suppose, the other really big Donovan song on this album. Due to being a bit Hey Jude in a way, in terms of being a song of two halves. The first half of which is Donovan telling a story of Atlantis in his away-with-the-faeries sott voce and the second half consists of him wailing away, “Way down, below the ocean – where I wanna be.” I gather Martin Scorsese is a big fan as it appears in at least two of his films and, like I keep saying, it’s fantastic. My favourite bit is towards the end of the second half, where Donovan improvises – I guess – “Glug, glug down”. I don’t know. It’s daft, but Donovan is daft – and that’s what’s great about him. He’s the right sort of daft, even though he wants to be wise and wastes his time by going around telling everyone how wise and influential he is when he’d be better off just being daft and letting people love him for it.

Following Barabajagal, the album, Donovan went off on a tax break year tour, which he bailed on and came home, to find his long lost love, Linda, whom he married and had babies with. And that, basically, was it for Donovan. At least as far as I’m concerned. There are, however, a couple of moments of inspiration that I might as well include.

HMS Donovan

Another double album, this time all of it aimed at kids – and it’s not all great, but some of it is fucking ace.

In my first year at university – in York – there was a great second hand record shop on Gillygate that’s long gone now. It was on the corner, near the St John’s Campus. Now, it’s a couple of different shops – one a bakers, one a hairdressers’, I think. It was a big shop and it was pretty much all vinyl in those days.

Due to my continually flashbulbing memory, I can pretty much remember the records I bought from that second hand shop, even if I can’t recall the name of the shop. I got Syd Barrett’s first two solo (and only) solo records there – original presses, I’m surprised I didn’t get them nicked from Desmond Ave, where plenty did go west. Other than that, I got the soundtrack to Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid because I was into South American Getaway from that – another great “song”.

The Syd Barrett records weren’t cheap, about £15 a pop which doesn’t sound like a lot for a record these days, but it was a lot more than I generally paid back then. HMS Donovan, which I’ve never seen before or since, set me back £20 in my first term of my first year, to the horror of Paul, the Croydon Christian, who lived above me in Fairfax House. He was beside himself. I don’t regret it, although I do regret that it didn’t have the poster that came with it when it was released.

It’s not everyone’s cup of tea – done by the artist who painted the cover of the album – and most of Gerry Rafferty’s solo albums (and ones with Stealer’s Wheel).

I do have a John Byrne (who referred to himself as Patrick) painting on my wall in the back room of our house, where I’m currently typing.

It’s a painting he was commissioned to paint by The Beatles for what became The White Album – or, really, The Beatles. I think of it as being called “A Doll’s House” because that’s what it was gong to be called before fucking Family, for fuck’s sake, brought out an album with that title and The Fabs changed their mind about calling it that. Which is a big shame because, due to its contents, The White Album sounds exactly like a spooky Doll’s House ought to. Note the picture of Yoko that John’s holding up. It’s a bit Rousseau, isn’t it? I’m not really a fan of Rousseau, but I do like John Byrne’s art. He was in an open relationship with Tilda Swinton for about ten years, which seemed a strange match – as strange as open relationships are in the first place. Still, each to their own, eh?

Anyway, HMS Donovan. The best track on it’s the first one – The Walrus & The Carpenter, adapted from the poem that Tweedledum & Tweedledee tell Alice in Through The Looking Glass – which is great all by itself, and one of the few classic children’s books that quite a lot of kids are aware of these days, even if they’ve only seen the Disney cartoon – which I don’t mind either. The books though? They’re outstanding. I used to have a colour illustration of The Walrus & The Carpenter on my phone case, until the phone conked out and my new one didn’t fit the old case. Now I’ve got Alice looking at the Cheshire Cat, who’s sitting in a tree. I fucking love the Alice books, me. I read them when I was a little kid and have continued to re-read them ever since. They’re often on my mind. I wrote a blog post about how being at Primary School made me think of the Walrus & The Carpenter in terms of a girl who was in my class there had a shit time that just kept getting worse, and how I didn’t do anything about it.

Anyway, if the songs on Donovan’s first effort at a children’s album were tossed off and nunty, this is the opposite of that. I’ve played it to plenty of people and, without exception, they all hated it, but they’re wrong because it’s the Sgt. Pepper of children’s songs. Astonishing, really. If Donovan had done nothing else but this, I suspect he’d still have a place in magazines aimed at boring, middle aged men like me. Not that you see much about this in such places, but then, there’s plenty of other Donovan things to write about. Like how he invented The Beatles’ White Album and Celtic Rock and how he wasn’t influenced by Bob Dylan at all when he first got famous…

Anyway, HMS Donovan is patchy – like Sgt Pepper’s is – but it’s a vast improvement on what he bequeathed to the little ones on AGFAFTAG.

Cosmic Wheels

In a lot of ways, Donovan was all about The 1960s. I don’t mean he invented the 1960s even though he probably thinks he did, but he’s an important part of them. He’s not The Beatles, no – he’s not even The Kinks, but he’s a bigger deal than just being some sort of Beatles hanger on. To understand the swinging sixties, I don’t think you can leave him out – despite how he makes a dick of himself almost every time he opens his mouth – the great Herbert that he is.

Being so tied up with a particular era meant that once it was over, so were the people most closely associated with it. The Beatles, of course, finished about in the nick of time. As did The Small Faces. The Rolling Stones evolved and were never just about Carnaby St anyway. The Kinks kept hanging on but, really, they evoke a sunny day in 1966 in London so well that once the 70s came along, nobody really accepted them as anything but what they once were. Much to Ray Davies’ chagrin.

In addition to being associated with one short era, what it means is that, periodically, they all have their big comebacks. Donovan’s tried a few times, none with very much success.

His first big comeback was in 1973 with Cosmic Wheels. HMS Donovan hadn’t set the world on fire, and I don’t expect anyone really thought it would. But Cosmic Wheels reunited Donovan with Mickie Most and it did alright, going top 20 in Britain and America. At the same time as he was recording it, Alice Cooper was recording Billion Dollar Babies in the same studio and Donovan sang on that too. Wikipedia claims that Donovan’s singing “helped propel” that song to number 1 on the charts. I wonder who made that claim? Personally, I’ve never heard it, or any other Alice Cooper songs, apart from School’s Out For Summer, so I wouldn’t know. Wikipedia also suggests that the glam rock explosion of the time meant that all the glam rock superstars were going around telling everybody how Donovan influenced them because he probably invented it along with everything else, but as they suggest David Bowie was going around singling Donovan out for praise when he was Ziggy Stardust – and I’m quite a big fan of Bowie, and I’ve never seen him mention Donovan, not that I’m infallible. Does Donovan edit Wikipedia pages for himself? He probably invented Wikipedia too. And the internet. So maybe he does.

Anyway, I eventually got hold of Cosmic Wheels, as you could find that in second hand shops pretty cheaply and, guess what? It’s alright. Sort of. Well, the song Cosmic Wheels is alright and I expect that schoolboys of the time enjoyed The Intergalactic Laxative, but that’s about it.

It goes to show that Mickie Most knew what he was doing, because the backing is great. Stabbing cellos, like T. Rex records of the time. The warbling girl backing singers sound like the music of the spheres and it all fits. For a glam rock record that doesn’t go for a Sweet or Slade pastiche, but focuses on T Rex’s more cosmic (dancer) records, it’s spot on. If any of the glam rock superstars were influenced by Donovan, Marc Bolan must have been at the front of the queue, especially with his airy fairy 60s Tyrannosaurus Rex albums that John Peel was such a fan of. Not that I could imagine Bolan admitting any influence from someone like Donovan, especially as it was true.

And that’s as far as I go with Donovan. I didn’t like anything else he did after this. In fairness, I didn’t like everything he did before it either but, like so much music by so many bands and singers, what I do like, I really like.

I’m not going to knock Donovan, he should be celebrated to a far greater extent than he is and the reason he’s not is because a) he’s too closely associated with a genre that fell so far from favour that people don’t even want to remember that it ever actually existed, b) Even if they do want to remember it, there are other bands and artists who’ll do the hippy dippy thing to a slightly more acceptable extent than Donovan’s records (especially American ones, Mamas & The Papas for one), c) He doesn’t half go on about how important he was.

And c) is the reason why the sort of people who probably would go on about him don’t. It’s an injustice, which is probably why he feels he has to blow his own trumpet so much. He was a very big deal and he did influence a lot of music and culture, but that culture is seen as being a bit shit now – especially after what punk rock did to it.

Those who still dig folk music now tend to look for a bit more of a serious thing from the bands of the past, and that means in the folk tradition – the Cecil Sharpe Child Ballad things. Pentangle – who I love, Fairport Convention – who I love bits of, Bert Jansch, Anne Briggs who I love. They’re the ones who retained a bit of credibility, but they were never pop music, and the folk scene’s a funny place.

You can’t sell out if you want folk credibility and Donovan, being as big as he was, and making such great pop records, is seen by such people as a bit of a sell out. And the people to whom he sold himself out to just aren’t that bothered.

It’s a shame, but the records are all out there now and there’s enough fantastic stuff on them that means that it’ll probably take his death to really bring it home what a great pop star he was.

And that’s the reality. Donovan was a fucking great pop star of the swinging sixties. Tuneful, funny and daft as a brush.

What more do you want?

One Comment Add yours